Style Guide: Arts and Crafts

We look back on Arts and Crafts style and highlight designers upholding the movement’s legacy.

We look back on Arts and Crafts style and highlight designers upholding the movement’s legacy. Celebrating quality construction, skilled craftsmanship, and the beauty of natural materials, the Arts and Crafts movement has renewed relevance in today’s hyper-commercialised world. Ideals of quality over quantity, ‘truth to materials’, and beauty in simplicity are making a resurgence, as concerns over economic and environmental sustainability are reflected by contemporary designer-makers.

Arts and Crafts designers railed against the plethora of poorly made objects and sham historical styles churned out as a result of growing industrialisation and commercialisation in Victorian Britain. Developing in the 1860s as a reaction against stuffy ornament-filled interiors, gaudy commercialism and industrial production, the Arts and Crafts movement sought to restore the link between beauty and utility, material and design, hand and object. Rejecting the division of labour in industrial manufacture as dehumanising, Arts and Crafts designers set up small workshops in which objects were made from start to finish by skilled craftsmen. Handcrafting and taking pleasure in work were seen as morally uplifting, and morality of manufacture was coupled with morality of design. ‘Truth to materials’ was the moral compass of good design. The inherent beauty of natural materials was celebrated and designers were to have a full understanding of the material being worked in order to produce well-designed objects fit for purpose.

The high moral seriousness of the Arts and Crafts movement might be a bit of a turn off. (It’s detailed in possibly the most tiresome tome in the history of design: News from Nowhere, by William Morris.) But a visit to one of the great houses of the Arts and Crafts movement, Rodmarton Manor in Gloucestershire, dispels any misgivings about the actual designs produced. Hallmarks of Arts and Crafts style include simple structural forms (used to emphasise the natural qualities of materials), exposed construction (such as wooden pegs and joints), tactile ergonomic design and organic patterns. All these are evident in the interiors at Rodmarton Manor, while the exterior draws on the bold forms of vernacular architecture in rural Britain.

Designed by Ernest Barnsley in 1909, the house features traditional Cotswold architectural details including gables, stone mullions, leaded lights and tall chimneys. Employing local craftsmen, it was built using local stone and tiles, as well as timber felled from the surrounding area. Much of the furniture was made for the house at Rodmarton workshops and includes designs by Ernest Gimson, Alfred and Louise Powell, Ernest Barnsley’s brother Sidney, and Sidney’s son Edward. Perhaps the very best work, and that which goes furthest to shake off the ‘backward provincial’ tag, is by Dutch émigré cabinet-maker Peter Waals.

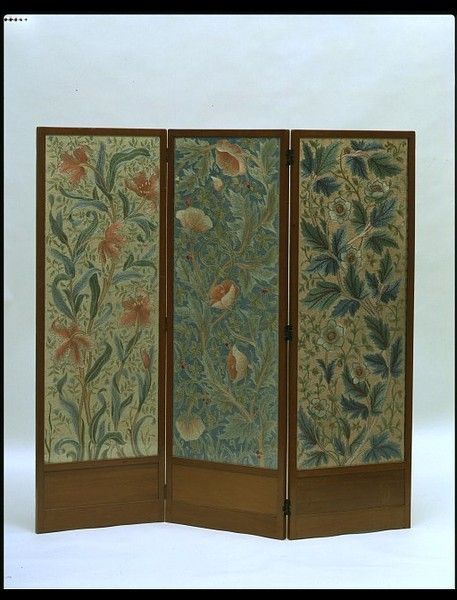

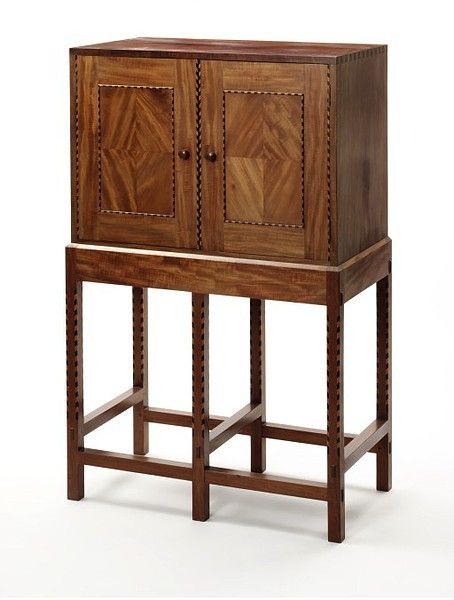

Waals produced two burr walnut writing cabinets for the drawing room at Rodmarton as well as numerous other pieces. Finished to a high lustre, the cabinets show off the beautiful grain of the walnut, featuring raised panels and drawers with chamfered edges, exposed dovetail joints, holly and ebony inlays, and handles with carved finger holds. The rooms at Rodmarton are large, and furniture was built to match: great dressers, chests and cabinets with multiple drawers, tactile grab handles and sliding wooden door catches. But the quality of detailing is remarkable: delicate inlays, turned, tapered and chamfered wood, and multiple timbers enhanced to bring out the grain. Oak floorboards are overlaid with bright hand-knotted rugs; whitewashed walls enhance feelings of light and space; curtains and drapes feature organic patterns based on floral and animal forms. In the library, a huge screen painted by Louise Powell depicts young ferns, spindly trees with delicate blossoms, and frolicking squirrels and birds. After visiting Rodmarton in 1914, C R Ashbee, an influential exponent of Arts and Crafts style, proclaimed that ‘the English Arts and Crafts movement at its best is here’.

Although the Arts and Crafts movement is associated with the country life, it had a strong cosmopolitan base. Arts and Crafts style was popularised by shops such as Liberty and Co. though which designers including C F A Voysey, Ashbee and William Morris sold their work. Liberty adopted Arts and Crafts as its signature style, and continues to produce fabrics by Arts and Crafts designers today. With the current resurgence of interest in craft, and the desire for quality over quantity in economically uncertain times, the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement are making a comeback. Contemporary designers are spearheading a revival of craftsmanship and traditional skills.

Tom Dixon’s Beat vessels and shades are made from hand beaten brass using a traditional, rapidly vanishing skill from Indian master craftsman. His pressed glass pendant lights are hand cast and each reflects the inclusions and imperfections of the manufacturing process. Dixon established the brand in 2002 with a commitment to reviving the British furniture industry, and his work draws on Britain’s craft heritage. Dixon’s Natural Slab chair has all the Arts and Crafts hallmarks. Crafted from solid oak with a deeply brushed surface, exposing the grain of the wood, visible wooden pegs fix the seat to the frame. Innovation is combined with traditional craftsmanship to create a space-saving, stackable dining chair. Dixon’s Offcut furniture range uses scraps or ‘off-cuts’ of oak that would otherwise have been discarded, and embraces the beauty of imperfection. Arts and Crafts ideals are united with current environmental concerns.

Anna Lockwood of Lockwood Design creates unique, one-off pieces of furniture. She specialises in traditional upholstery techniques and uses natural materials such as hessian, coir fibre, horsehair and calico. Sourcing vintage and antique pieces as well as providing a complete restoration service or a simple recover, her work is environmentally friendly and craft driven. The Holland occasional chair has an Arts and Crafts look about it, with a turned wood frame and seat upholstered in orange felt. The Benjamin wing armchair has the same 100% wool felt upholstery and beautiful bees-waxed legs. It wouldn’t look amiss at Rodmarton Manor.

Running an apprenticeship scheme and employing and training up workers from the local area, Benchmark continues the legacy of the Cotswold Arts and Crafts movement responsible for Rodmarton Manor. Producing contemporary classics with sustainability in mind, Benchmark is founded on a belief in the timeless appeal of good design. Celebrating high quality materials and traditional craftsmanship, the furniture collection is hand made to order from start to finish in the workshops in West Berkshire. The angle-fronted Admiral Cabinet in American black walnut with lacquer finish epitomizes ‘truth to materials’, working to bring out the natural beauty of the wood grain. Crafted from solid fumed oak with a lacquer finish, the Jack Pedestal dining table recalls a design by Ernest Gimson in the Drawing room at Rodmarton. The Darcey table and Furrow sideboard evoke the simple sophistication of Arts and Crafts furniture.

Good design and quality construction never date. Celebrate design innovation and invest in the future of traditional craft skills.